Sri Lanka presents a familiar but increasingly costly paradox. The country has near-universal female literacy, strong educational outcomes for women, and better health indicators than many peers in South Asia.

Sri Lanka presents a familiar but increasingly costly paradox. The country has near-universal female literacy, strong educational outcomes for women, and better health indicators than many peers in South Asia.

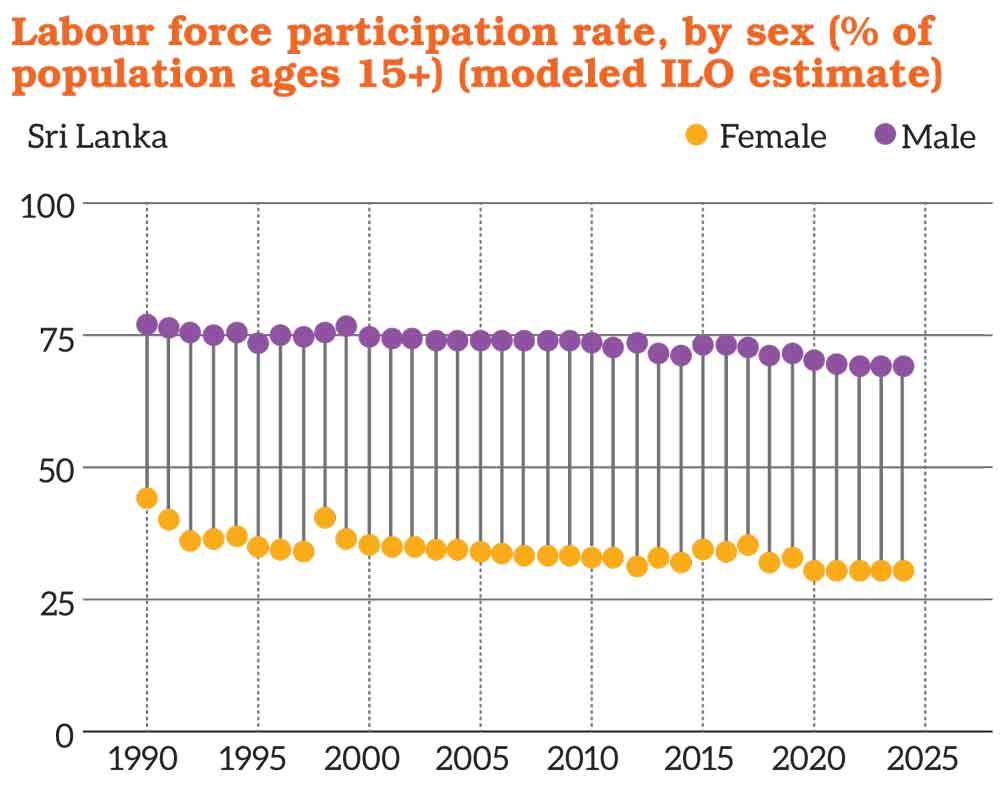

Yet only around 31–32 percent of women participate in the labour force, far below global averages and well below what Sri Lanka’s human capital profile would predict. In the context of fiscal fragility, population ageing, and repeated climate-related shocks, this gap is no longer a social concern alone. It is a macroeconomic constraint.

From a growth perspective, Sri Lanka can no longer afford to underutilise half of its potential workforce. Demographic ageing, sustained outward migration of skilled labour, and limited fiscal space mean that future growth will depend less on capital accumulation and more on labour supply and productivity.

Benefits

Raising female labour force participation would expand the effective workforce, lift household incomes, support domestic demand, and broaden the tax base. International evidence suggests that narrowing gender gaps in employment can generate sizeable and durable gains in output, particularly in middle-income economies facing demographic transition. For Sri Lanka, this is not an abstract benefit. It is central to stabilising public finances and sustaining recovery.

The case is equally compelling at the household level. Rising living costs, income volatility, and accumulated debt have placed families under severe strain. These pressures are magnified by climate-related disasters. The recent cyclone displaced communities, disrupted livelihoods, and intensified unpaid care responsibilities, which continue to fall disproportionately on women. In this context, women’s economic participation is a key source of resilience. Dual-income households are better able to absorb shocks, recover from income losses, and sustain spending on education and health. Without broader female participation in paid work, climate shocks risk entrenching inequality rather than remaining temporary disruptions.

The persistence of low participation is not explained by lack of education or capability. Instead, it reflects a set of structural constraints that have remained largely unaddressed. Rigid work arrangements, limited access to affordable childcare and eldercare, unsafe and unreliable transport, and weak pathways back into employment after career breaks act as binding constraints. Evidence across countries consistently shows that high childcare costs and limited availability reduce women’s labour supply, particularly for mothers of young children, even where education levels are high. Social norms around caregiving continue to matter, but they interact with institutional failures rather than operating in isolation.

Need for coordinated action

Addressing these constraints requires coordinated action by both government and the private sector. For firms, increasing female participation should not be framed as corporate social responsibility, but as a question of productivity and talent retention. Flexible work arrangements, including part-time roles, hybrid work, flexible hours, and structured return-to-work programmes, can materially improve retention and re-entry rates. Advances in digital infrastructure have expanded the scope for such arrangements, particularly in services, finance, education, and professional sectors where Sri Lanka has comparative potential.

Artificial intelligence should not be treated as a solution in its own right. However, when embedded within supportive labour and social policies, it can act as a facilitator that amplifies reform. AI-enabled platforms can expand access to remote and flexible work, reducing constraints linked to transport, location, and care responsibilities. Personalised digital training tools can support women’s re-entry into the workforce and transition into higher-productivity sectors, while technology-enabled care services can improve the efficiency of childcare and eldercare provision. These gains will only materialise if matched by public investment, regulatory safeguards, and targeted skills development.

Govt. policy

Government policy has a catalytic role. Labour regulations and social protection systems must support flexible employment without eroding worker protections. Public investment in affordable childcare and community-based care services would address one of the most significant barriers to women’s participation. Safer and more reliable transport systems are equally critical. Skills policies must also be better aligned with labour market demand, particularly in digital, care, and green sectors, where employment growth is likely and women’s participation can be scaled more rapidly.

Post-disaster recovery strategies deserve particular attention. Women are often treated as recipients of relief rather than as economic actors central to reconstruction. Livelihood restoration programmes, local employment initiatives, and access to finance should be explicitly designed to support women’s re-entry into paid work and entrepreneurship. Failing to do so risks locking in the economic scarring effects of climate shocks.

Increasing female labour force participation is not simply a matter of adding women into existing labour market structures. It requires redesigning work, policy, and institutional support to reflect economic realities. For Sri Lanka, this is not an optional reform agenda. It is essential to fiscal sustainability, household resilience, and long-term growth. The cost of inaction is measurable, and the opportunity cost of continued underutilisation is one the country can ill afford.

References:

https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/economies/sri-lanka

https://nhrdc.gov.lk/nhrdc/index.php/publications/sri-lanka-human-capital-summit-report-2024

(Cathrine Weerakkody is a lecturer on Finance Accounting at the University of Buckingham, United Kingdom)

Source:

dailymirror.lk

.png)

.png)

.png)

0 Comments